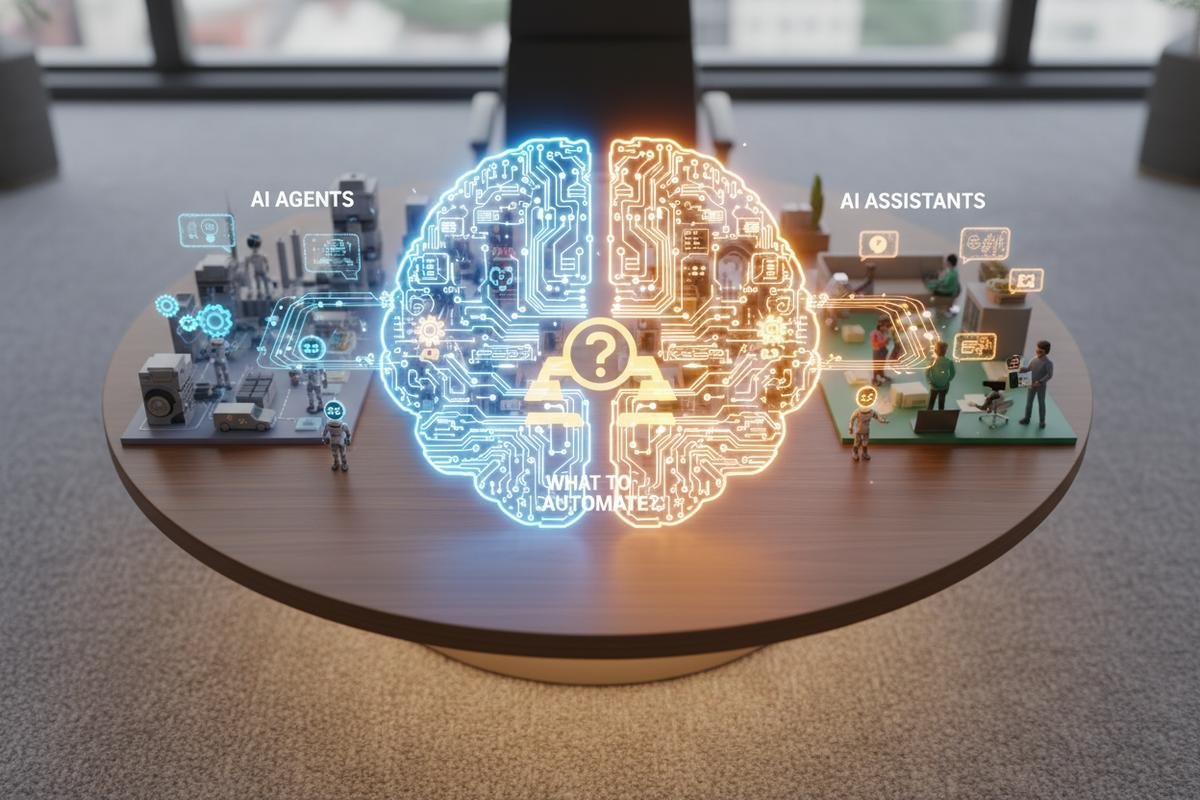

AI Agents vs. Assistants: Deciding What to Automate

Understanding the distinction between an assistant (which waits for you) and an agent (which acts for you) is the single most important factor in your automation strategy. This guide details exactly when to deploy each, specifically for UK operations navigating the post-2025 Data (Use and Access) Act landscape.

The Core Distinction: Reactive vs. Proactive

To make the right decision, strip away marketing and look at functional behaviour. The practical difference is who initiates action and how much autonomy the system has.

AI Assistants are reactive. Many users find tools such as Microsoft Copilot in Word or chat interfaces on search platforms operate only when prompted. They require a human to supply the next instruction and to validate outputs before any external-system change is made.

AI Agents are proactive. They accept a goal, plan multi-step actions, call tools and can change external systems without a prompt at every step. Open-source examples such as Auto-GPT show the loop of planning, action, observation and revision. Agents suit continuous monitoring, cross-system orchestration or long-running background tasks – but they need governance and constraints.

3 Common Implementation Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

1. Deploying Assistants for multi-step process work

A common issue is assuming a chat interface can manage workflows end-to-end. For example, telling a chat assistant “manage my inbox” typically yields draft responses for a human to send; it will not autonomously monitor incoming mail or authenticate into systems without an agent scaffold.

Try this: start by mapping the process into discrete APIs and retries, then build a minimal agent that calls those APIs. ☐ Identify required APIs. ☐ Define retry and error-handling behaviour. ☐ Test in a sandbox.

2. Granting broad permissions without oversight

Many projects fail because they grant an agent write rights too early. A typical failure is an agent that “optimises” CRM records and inadvertently overwrites fields.

First, adopt least privilege: start with read-only access, run in a mirrored sandbox and only elevate privileges after validated runs. ☐ Configure read-only roles. ☐ Prepare a sandbox with synthetic or anonymised records. ☐ Log and review every write before approval.

3. Treating agency as a cost-free improvement

Agents can loop for long periods while exploring solutions, consuming compute and API budget. A common consequence is unexpected bills and degraded performance.

Start by setting operational limits: rate-limit calls, set budget quotas and implement checkpointing so an agent cannot iterate indefinitely. ☐ Define per-agent CPU/API budgets. ☐ Implement checkpoint saves. ☐ Configure alerts for budget thresholds.

Specific mistakes to avoid

Many teams make predictable errors; here are concrete ones to watch for and alternatives to consider.

- Mistake: Letting agents operate on production data immediately. Instead: Use a mirrored sandbox with synthetic or anonymised records until behaviour is validated. ☐ Create sandbox copies. ☐ Populate with synthetic data.

- Mistake: No clear kill-switch or emergency rollback. Instead: Build an accessible termination API and automated backup/restore for any system the agent can change. ☐ Implement termination API. ☐ Automate backups before agent writes.

- Mistake: Expecting agents to replicate nuanced brand voice. Instead: Use assistants for drafts and keep publishing decisions human-led. ☐ Use agent to draft only. ☐ Require human sign-off for publishing.

- Mistake: Poor logging and no human review windows. Instead: Implement immutable audit logs and periodic human-in-the-loop checkpoints. ☐ Enable immutable logging. ☐ Schedule review checkpoints.

When NOT to Use Autonomous Agents

Despite the promise, there are clear zones where removing the human from the loop is reckless or unlawful. The Information Commissioner’s Office advises caution on significant solely-automated decisions; see ICO guidance on automated decision-making and profiling.

Specific ‘do not use’ scenarios include:

- High-stakes legal or financial decisions: Loan approvals, hiring shortlisting that produces regulatory effects, or eviction notices. These require documented human decision-making and appeal routes. ☐ Keep final sign-off human.

- Safety-critical systems: Medical device control, industrial safety interlocks or real-time life-support decisions. Agents should not take autonomous control without certified safety cases. ☐ Require certified safety approval.

- Crisis communications and PR: Public statements during a major incident should not be auto-published. Tone and accountability need human oversight. ☐ Hold messages for human review.

- Sensitive personal data processing: Where errors can materially harm individuals, keep humans in the loop for final decisions. ☐ Restrict agent access to sensitive records.

Decision Checklist: Assistant or Agent?

Use this expanded audit and treat each box as a gate. If fewer than four boxes apply, stay with an Assistant.

☐ Is the goal objective and measurable? (e.g., “reorder item when stock < X” vs “choose a nice gift”).

☐ Are the steps deterministic? (Can you write a Standard Operating Procedure for the sequence?)

☐ Can you tolerate trial-and-error behaviour? (If the agent tries an incorrect path, can automatic recovery or human intervention handle it?)

☐ Is asynchronous operation acceptable? (Do you have monitoring and SLAs that tolerate minutes or hours?)

☐ Do you have granular access controls and audit logging? (Can you trace every API call and revert changes?)

☐ Is regulatory risk low? (The task should not create legally binding outcomes without human sign-off.)

Trade-offs and Consequences – More Detail

Moving from Assistants to Agents alters several operational dimensions. Be explicit about trade-offs before procurement or rollout.

Cost vs. Benefit: Agents consume more CPU and generate more API calls; the benefit is saved human time and continuous operation. Many organisations automate low-value repetitive tasks first and audit ROI before scaling.

Latency vs. Autonomy: Assistants answer interactively; agents may take longer to arrive at an outcome. If speed is critical, prefer assisted workflows with human oversight rather than full autonomy.

Transparency vs. Effectiveness: Agents can produce results without exposing intermediate reasoning, reducing explainability. For regulated contexts, log plans and decisions or use hybrid designs where an assistant summarises the agent’s plan before action.

Security and Data Governance: Agents that connect to multiple systems increase attack surface. Enforce least privilege, token rotation and network segmentation. Integrate with your identity provider and secret management system.

Actionable Steps to Implement Agents Safely

Start by running a small, well-governed pilot. Below are sequential steps you can follow.

Step 1 – Define the goal and success criteria

First, state the objective in measurable terms and write acceptance criteria. ☐ Document the goal. ☐ Define KPIs and safety thresholds.

Step 2 – Map the workflow and APIs

Identify each external system the agent will call and the exact API surface required. ☐ List APIs and required scopes. ☐ Document retry and error flows.

Step 3 – Build a sandbox and synthetic dataset

Start in a mirrored test environment populated with anonymised or synthetic records. This limits blast radius while you iterate. ☐ Create sandbox environment. ☐ Import synthetic/anonymised data.

Step 4 – Implement controls and observability

Deploy least-privilege roles, immutable audit logs and a visible dashboard for agent activity. ☐ Implement RBAC. ☐ Enable immutable logging. ☐ Configure monitoring and alerts.

Step 5 – Add safety gates and kill-switches

Provide manual and automated shutdowns, plus automated backups and rollback procedures. ☐ Expose a termination API. ☐ Schedule automated backups prior to writes.

Step 6 – Limit operations and cost exposure

Set rate limits, API quotas and max iteration counts so an agent cannot run uncontrolled. ☐ Apply rate limits. ☐ Configure budget alerts and max iterations.

Step 7 – Human-in-the-loop rollout

Release the agent with human checkpoints: let it propose actions for approval before full automation. Gradually relax oversight as confidence grows. ☐ Start with human approval required. ☐ Move to partial automation after repeated validated runs.

Try this: run a two-week pilot that follows Steps 1-4, then review outcomes with stakeholders before Step 5. If issues appear, pause and revert to the sandbox.

Practical Scenarios and ‘Instead of X, consider Y’ Comparisons

Concrete examples help translate these trade-offs to real decisions.

Scenario – Inbox triage: Instead of giving an agent full outbound email privileges to “handle my inbox”, consider a hybrid: the agent labels, prioritises and drafts replies and a human reviews and sends. ☐ Agent drafts only. ☐ Human approves outbound messages.

Scenario – Supplier reordering: Instead of granting full procurement rights, have the agent monitor stock, create reorder suggestions and kick off purchase orders only after human sign-off for first N runs. ☐ Agent monitors stock. ☐ Human approves first N reorders, then review.

These steps and controls reduce implementation risk while letting you realise productivity gains. Start small, instrument heavily and iterate based on observed behaviour.